Meet Dr. Haubenreich

Jacob Haubenreich joins the faculty by way of the University of California, Berkeley, where he received his Ph.D. in 2013.

Jacob Haubenreich joins the faculty by way of the University of California, Berkeley, where he received his Ph.D. in 2013.

Starting out as a pre-med student, Dr. Haubenreich later found new challenges and passions when he shifted his focus to German Studies.

Read an interview conducted with him below.

INTERVIEW

So how did you get interested in German Studies?

When I went to college I planned, like so many students do, to study medicine. I’d always been interested in math and science, and I did the whole pre-med thing—and did quite well in it, until I decided to switch to German Studies, at which point I stopped doing so well! I found my humanities courses to be more challenging, or challenging in a very different way, than my science courses.

I had studied German in high school and continued in college to meet requirements. And I’d always enjoyed reading literature, but something was lacking—it was all about writing short essays on some theme, and reading what seemed a series of random works by random authors.

Then in college I took a course on German literature in translation, and things started coming together—I came to see how the literature was part of a wider cultural context. I began to see how literature, philosophy, and art are not only shaped by the events in the ‘real world’ but shape how we experience the world. I learned that things that I had merely liked or found interesting were actually really important.

How is literature important?

Our lives are shaped by our experience with literature. Our personal biographies take a narrative form, for example. Lives are stories. Fiction isn’t unreal, or just an attempt to mirror “the real world”: it influences how we understand and live our lives. And that’s just one way language shapes experience.

And how do you think language shapes experience?

My own approach to this sort of thing curiously mirrored developments in theoretical approaches to literature over the past few decades. I started by being interested in how historical and cultural context influenced the books I liked, then took an interest in the question of literary genre—how a piece of literature is shaped and limited by the sort of work it is taken to be. [Our lives, too, are obviously influenced by history and culture, and by the type of person we take ourselves to be—and this history, culture, and character types are heavily influenced by our experience with literature (including things like movies and TV).]

I turned then to the idea that texts are self-contained wholes, that texts and fiction aren’t just products of a culture or an author but entities of their own.

I then became more interested in language itself. I found myself teaching students about the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the notion that language fundamentally shapes thought so that, in the extreme case, if one language has a word for something but a second language doesn’t, the speakers of the second language can’t share the thoughts of the those who speak the first language.

Finally, I’ve landed in the study of materiality, the notion that the physical form of a text, and our own bodily experiences in reading that text, are a fundamental part of the experience of literature.

Could you explain a bit more how this ‘materiality’ stuff works?

Texts are physical things, part of the real world, not something that only represents or mirrors the real world, and our experiences with texts are as real, and as physical, as any other experience we have. So the physical form of a text matters, it shapes our experience of the text. This is something that’s increasingly obvious to us these days as new forms of electronic media change our experience of reading.

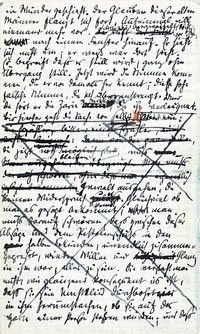

Perhaps it makes sense—since we’re dealing with the claim that certain concrete things matter!—to talk about my dissertation project. I went to Switzerland to look at the manuscript of the only novel by Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926), The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge. One theme of Rilke’s work is that reality is in flux; he was one of the authors who focused on how unsettling the early 20th century was, what with all the changes going on in society, technology, culture, and politics.

And looking at the manuscript (pictured, left) helps one see how Rilke’s world was in flux: it is full of various sorts of cross-outs, different colored corrections, etc. Clearly writing for Rilke was a destabilizing sort of process. So the physical form of Rilke’s manuscript shows us that the process of writing resembled ‘real life’ as his fictional character experienced it, and as Rilke himself experienced things. ‘Life’-‘reality’-‘fiction’—they all come together, and one can see it with one’s own eyes by looking at that manuscript! So what started as just one chapter in my dissertation took over my whole project, as I came to study what we could learn about Rilke’s work from close study of this manuscript.

And looking at the manuscript (pictured, left) helps one see how Rilke’s world was in flux: it is full of various sorts of cross-outs, different colored corrections, etc. Clearly writing for Rilke was a destabilizing sort of process. So the physical form of Rilke’s manuscript shows us that the process of writing resembled ‘real life’ as his fictional character experienced it, and as Rilke himself experienced things. ‘Life’-‘reality’-‘fiction’—they all come together, and one can see it with one’s own eyes by looking at that manuscript! So what started as just one chapter in my dissertation took over my whole project, as I came to study what we could learn about Rilke’s work from close study of this manuscript.

So does this affect your teaching here at SIU?

I think it gives us a new way of looking at texts in the classroom. Most commonly, when we read texts, we ask “what does this mean?” or “what is the author trying to say?” These questions are certainly important, but there are other questions we can ask. It’s also important to think of texts as linguistic art objects that are constructed in different ways and produce different effects in us while we’re reading.

For example, when German sentences – as they are want to do – go on and on and on, this can sometimes drive us mad as readers! And when we’re reading about a person who is driven mad through her constant surveillance by the Stasi in East Berlin, then we experience, while reading, something of what the character experiences. In my writing course this spring, I’m also going to have students experiment with writing in different media. Students will write some essays entirely by hand, and think about how the process and end result is different than writing on the computer. We’ll also experiment with translating stories into text message and twitter format, to think about how the media of writing shapes the content of the text.

In this way, how texts were written and their material form is part of how they make their meaning. And from this, I think, we can also learn more about how we ‘author’ our own lives. We not only interpret events in our lives just like we interpret texts; in a sense, our lives are like texts that we play a part in authoring.